Testing school children is a very old tradition. At the school level, every teacher thinks about how they will know that students are learning their curriculum. Summative assessment, e.g., giving a quiz at the end of the chapter or unit has also been the traditional way to assess student learning. The big testing development in classrooms has been in formative assessment, the idea that giving more informal assessments along the way, helps both student and teacher. For example, documenting that students are not getting the vocabulary learned early on, helps teachers go back over it, and helps students really learn it, in time for the end of course test or quiz. But the increase in testing at the state level has overshadowed the developments at the classroom level. Might this be the time to look into classroom level testing ideas in order to inform national policy?

Increasing Accountability

Since the 1980s, state testing has radically increased. At the state level the increase in testing is tied to the definition of increased accountability. For example, the No Child Left Behind law of 2001 specified that every student, K-12, would be “proficient” on state tests. Many years later, with the help of statisticians and others, who had protested that this was an impossibility, the law was softened and changed. So by five years ago, many policymakers and state level education officers finally understood that increased accountability could not be improved by increased testing. But the wheels of increasing the test, increasing the amount of time, and increasing the number of times it was given, speeds on. Increasing the specificity with which the state holds teachers accountable for the delivery of curriculum was a hard trend to slow down. In fact, the wheels are only now slowing because of two things: The meaninglessness of the outcome reports from over-testing at the state level, and the opt-out movement, i.e., the number of students who have opted out from state testing.

Meaninglessness of Testing Outcome Reports

Supporters of more testing at more grade levels were chagrined to find out two things: The reports of their testing was telling them less and less and students were not making achievement gains as predicted. Another test, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), confirms that results were not improving. States were reporting vastly different things and some states were reporting things that cannot be, such as the Texas Miracle, where all students increased their scores by high percentages in a short few years. As the data became more unreliable, states refused to yield to the meaninglessness and even tied teacher evaluations to the outcome scores of their students, supported by federal grants that specified this alignment. If states did not comply they would lose the chance to apply for these large federal grants.

Opting Out

With the states competing for a limited number of Federal grants decided through a lottery, and these grants specifying test results tied to teacher evaluation, there was a growing unrest at the school level about over-testing and many verbal anecdotes that parents were becoming fed up. No one noticed that the NAEP test was showing no change in student achievement in its sampling of the states, even though states had increased standards and testing. The NAEP is a very admired national test, given to sub-sets of students in parts of a state, in at least half of the states, every year. This yellow light of caution was joined by parents who finally said, “my kid is not taking the state test this year.”

Numbers and Accountability

There are always a few hundred students who don’t take the state test every year, whether for sickness or transfer between schools. But now there are many students not taking the test. In New York State, for example, something like 200,000 students did not take the state test this year. A reliance on state tests for accountability and for teacher evaluation—approximately 18% of each teacher’s evaluation score is tied to state test scores of their students—now is threatened, statistically.

New Student-Centered Learning Policy?

So where do we go from here? Luckily, the reauthorization of No Child Left Behind, is currently underway at the federal level. The new law will address this over testing, and will take some of the Federal push away from the Secretary of Education. But putting this issue back on the states’ policy agenda will mean that states now have to reconsider what is the best use of testing, how can we not over test, and what is the best way to hold all of us accountable, and together, for increased teaching and learning?

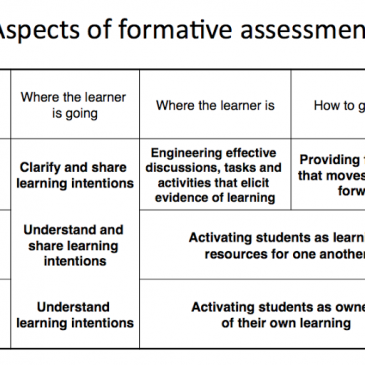

If more informal testing, under the broad idea of “formative assessment,” reveals better assessment of student learning, might a sample of local examples be used to inform a national estimate for learning? Instead of high stakes punishments, formative assessment sampling could be used in the same way we use a thermometer, that is to say, taking the temperature in order to understand one aspect of the patient. Why not use formative assessment to sample more generally how some of the students in a classroom, some of them across a grade level, a part of them in a school or a part them in a district are doing? And then, could we use these results to target schools for improvement? Wouldn’t it make sense to send resources and fund peer-to-peer professional development to schools in need of improvement based on informal assessment? If we can construct new policies around student-centered learning that benefit all of us, from student to teacher to parent we might increase the national estimate of learning while also improving it. My answer is to construct new policies around student-centered learning that benefit all of us, from student to teacher to parent. See my other posts, or my website, schoolworkslab.org, for more on this!

(Featured Image, “Aspects of Formative Assessment,” Wiliam, D. (2010) Innovation that works. Workshop at SSAT conference, Birmingham, Novemner. Retrieved 28 November 2010 from the World Wide Web:http://web.me.com/dylanwiliam/Dylan_Wiliams_website/Presentations.html)